Screech Timon ââåfloating Worldsã¢ââobtaining Images Art Production and Display in Edo Japan

Obtaining Images – Fine art Production and Display in Edo Japan

by Timon Screech

Redaktion Books (published with the assistance of The Nippon Foundation), London (May 2012)

384 pages including glossary, chronology, references, bibliography, acknowledgements and index, copious colour illustrations

ISBN 978 186189 8142

Review by Sir Hugh Cortazzi

Professor Timon Screech is Professor in the History of Art at the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), University of London, and is a Japanese art adept who has fabricated a detail study of the art of Tokugawa Nippon.

Obtaining Images is a scholarly written report of painting in the Edo or Tokugawa period. During the two and a half centuries between the commencement of the seventeenth century and the re-opening of Japan to the Due west presently later the middle of the nineteenth century Japanese artists produced paintings which are among the finest anywhere in the world. Screech's book not just analyses the factors which influenced Japanese artists but also provides a historical survey of the large number of unlike styles and schools of Japanese painting. It is total of fascinating insights and will be invaluable to all who desire to know more about and sympathize Japanese art at its apogee.

In his introduction Screech reminds his readers that paintings were not but important for their visual impact. They also reflected the status of their owners and of the painters themselves. Screech accordingly devotes the beginning part of his volume to a word of 'the mechanisms of artistic product and display.'

His first chapter is entitledLegends of the Artists in which, amidst other legends, he exposes the myth of the 'Superlative Painter.' Chapter Ii entitledAuspicious Images reviews the traditional themes so oftentimes establish in Japanese paintings such as dragons,kara-shishi (唐獅子- Chinese lions),kirin (麒麟- horse dragon) and thehōō ( 鳳凰-phoenix). Leopards and tigers were not found in Japan just were depicted for case in a famous screen by Sanraku Kano [狩野 山楽], where Screech explains that the two animals were regarded as 'he and she tigers.'

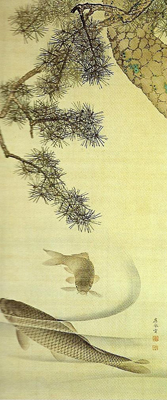

He explains various conceits used past Japanese painters such as those reflected in the ii images below:

1. (Left) Mōkari (alternative reeds) is a pun on the word mōkaru (儲かる- brand money) in this early on 19th century painting by Ippō Mori [森一鳳]

2. (Correct) Pines (shō [松] is theon reading ofmatsu(pino) and carp (ri [鯉] is theonreading ofkoi (carp). The 2 combined would readshōri [松鯉] which written with different characters mean "victory" [勝利]. Painting by Ōkyo Maruyama [円山 応挙].

The next chapter on buying and selling begins by describing the six standard painting formats – mitt scrolls, albums, hanging scrolls (kakemono – 掛物) which included diptyches and triptychs, screens which might be single leaf or folding, sliding screens (fusuma – 襖) and fans (sensu anduchiwa -扇). Screech goes on to give some fascinating insights into social mores in Tokugawa Japan. He points out that status carried with it obligations when it came to ownership and giving abroad pictures. Some painters eastward.g. of the Kano school received official salaries and were regarded equally the aristocracy. Their 'ateliers would not entertain commissions from commoners (Page 82).' 'Specially prickly were the gentlemen amateurs like Taiga and Buson' who saw themselves as samurai. Equally such they could non demean themselves to go involved in commercial transactions.

Screech in the concluding chapter of part 1 entitledThe Ability of the Image deals with religious art, which in the Edo period meant Buddhist paintings and images. This enables him to discuss such meaning Edo era sculptors as Enku. He notes that a not bad deal of secular painting was preserved in temples which tended to be amend preserved than secular buildings, Some of the finest Kano school screen paintings are indeed to exist plant today in Kyoto temples such as the Chionin [知恩院] and Nishi Honganji [西本願寺] in Kyoto.

In part two Screech provides an informative survey of the different schools of painting in the Edo menses. He starts with an account of the Kano school. He notes that Tan'yū Kano [狩野 探幽] who arrived in Edo in 1622 was given formal military machine rank and 'they ran their ateliers with the punctiliousness of all other shogunal officers (page138).' The Kano school was 'role of the government.' They had their own cloak-and-dagger text book setting out 'their ideologies and values, its categories of subject field affair, its historical lore and its protocols and pedigrees (page 139).'

The Kano school did not change with the times. They were forbidden to conform.

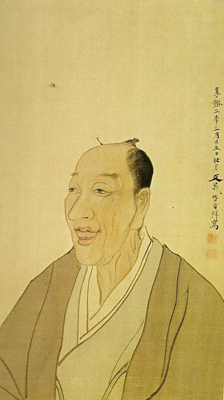

Screech deals next with portraiture where the Japanese approach differed greatly from the European. There was 'no thirst for portraits of people to whom one was non in some way connected (page 167).' In Tokugawa Japan visitors to the shogun did not look at him but kept their eyes down to the flooring. Portraits tended to exist deputed when an individual was approaching death. They mostly showed the sitter 'looking to the left, that is, their right. The nigh honoured position was facing south, looking towards the sun and important people routinely saturday that way. Since a portrait should be treated like the person, respect demanded it be hung on a north wall.' It was rare for a portrait to show the sitter other than in a formal posture. Bunchō Tani'south [谷 文晁] posthumous portrait beneath of Kenkadō Kimura [木村蒹葭堂] which shows him grin and in the act of talking is an exception to the general do:

The adjacent affiliate is entitled perhaps rather oddlyJapanese Painting. It deals firstly with the Tosa school which was associated with the court and 'concentrated on Heian poems and tales, and the birds and flowers that appear in them.' Kōetsu, Sōtsu, Kōrin Ogata [尾形光琳] and Hōitsu, often considered members of a separate Rimpa school are covered in divide subsections of this chapter.

Chapter Eight is entitledPainting within the Heart. This covers the literati painters and explains what is meant bynanga(南画- Southern paintings). This manner had no geographical connotations, merely rather denoted the way in which the painter depicted his subjects. Landscapes and even flowers and copse were not depictions of real scenes but were imaginary from 'within the breast.' Within this chapter Screech too covers the Ōkyo Maruyama [円山 応挙] and Shijō schools and Jakuchū Itō [伊藤 若冲].

Chapter ix is entitledFloating Globe (ukiyo). Screech explains that in the Yoshiwara (cherry-red light commune) and the theatre, which were central to the 'floating world,' the rigid grade distinctions of Edo Japan became blurred and the classes mixed. This chapter covers aspects ofukiyo-eastward, but is not intended as a history of the art of the Japanese print which impressed western observers and artists so much in the nineteenth century. Yet it seems a little odd that such an outstanding artist every bit Sharaku (Tōshūsai) [東洲斎 写楽] is not mentioned.

The final chapter is devoted to a discussion of artistic contacts with the W where perhaps the well-nigh well known Japanese creative person who reflected western influences was Kōkan Shiba [司馬 江漢]. His picture of birds in a wintertime landscape with a western city in the background is shown on the back cover of this book.

Kōkan Shiba: Birds in a Winter Landscape belatedly xviiithursday century

Western influences likewise had an touch onukiyo-e every bit can be seen in this charming print past Harunobu Suzuki [鈴木 春信] showing a daughter looking surprised to see the shadow cast by her umbrella:

In such a lavishly produced volume I was surprised that no Japanese characters were included. In the past when type had to exist set past paw it was understandable that Japanese characters were eschewed, only in that location is no difficulty these days in introducing characters into books in English. I would have specially welcomed the press of the names of Japanese artists in Japanese characters. They could too have been used beneficially for students with some knowledge of the Japanese language when Japanese poems are quoted.

Screech excuses the fact that his volume does not cover calligraphy, but it would in my view take added to the value of this work if information technology had included fifty-fifty a brief chapter on the great calligraphers of Edo Japan. Calligraphy was such an of import feature of Japanese ink painting.

Screech refers briefly to such pop pictures asOtsu-e, but his book is primarily about 'loftier art' and he has non been able to devote infinite to pic books which became then pop in Edo Japan.

The volume does not claim to be a history of Edo art simply only of images produced in the Edo period, but the frontiers of fine art particularly in Nihon merge so easily that imagery becomes of import not but for lacquer ware, briefly mentioned in the context of Kōrin Ogata (page 223), but also for the hugely important field of Japanese ceramics.

This book is already a lengthy 1 and information technology would be wrong to make too much of what it does not embrace and indeed does not claim to embrace. Every serious student of Japanese fine art will desire to read and to possess a copy of this of import and informative book, if only in order to be able to consult information technology equally necessary.

murray-priorcabou1994.blogspot.com

Source: https://www.japansociety.org.uk/review?review=342